IN THE FIRST EPISODE OF "THE ARCHIPELAGO", YANNIS-ORESTIS PAPADIMITRIOU DISCUSSES WITH CHRISTOPHER KING ABOUT HIS CONNECTION TO EPIRUS, HIS NEXT STEPS IN PRESERVING ITS CULTURAL HERITAGE AND HIS VIEWS ON THE ONGOING BATTLE BETWEEN AUTHENTICITY AND MODERNITY, STILL SEEKING A RESOLUTION.

Read MoreAthens Insider — Christopher King: An Evangelist for Greek Demotic Music

Christopher King’s first experience of hearing an Epiriot lament, by violinist Alexis Zoumbas, on a 78rpm recorded in 1926, sent him into a cathartic trance. Searching for a connection, Grammy-winning producer and curator King spent years researching and archiving music recorded between 1907 and 1960 from the rural hinterlands of mainland Greece and its islands. Several compilations of Epiriot music followed, and his critically-acclaimed book, Laments of Epirus received praise for drawing a wider interest into the forgotten sounds of demotic music, and into the evolution of song itself. For King, who hopes to find a permanent home in Greece for his archives, the haunting, guttural music of Epirus is both a “living link to antique Greek folkways” and a cathartic remnant of “a more ancient way of being”. This demotic Greek music may not be to everyone’s taste, concedes King, but copious amounts of tsipouro will convert most to its powerful pull.

Hari Kunzru interviews Christopher King

Hari heads down to the foothills of Virginia, where a legendary collection of blues records holds the key to understanding the insidious separation of “Black” and “white” culture.

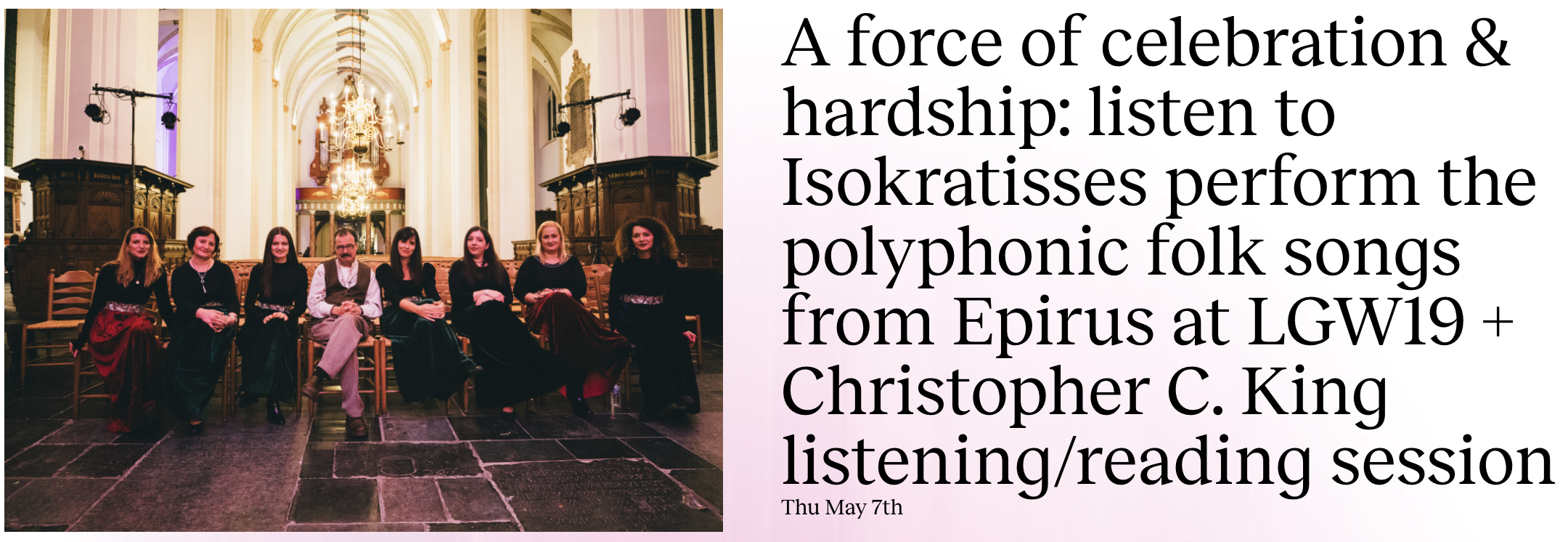

Christopher C. King Presents Polyphonic Group Isokratisses and a Listening/Reading Session in Utrecht, Holland

On November 9, 2019, the Greek polyphonic vocal ensemble Isokratisses gave a rare performance at the Jacobikerk during Le Guess Who? Festival in Utrecht, The Netherlands. Founded by Anna Katsi, the group dedicates itself to the polyphonic singing of Poliçan, an ethnic Greek village in southern Albania. All the members are women who developed their musical experiences together since their childhood; the project represents the desire to maintain a locality in the way of singing, as something that comes to life again through their voices.

Now, Le Guess Who? releases the full recording of the performance, as well as a listening and reading session by author, producer, archivist and musicologist Christopher C. King that preceded the concert.

The Healing Music of Epirus | Christopher C. King | TEDxAthens 2019 Main Stage

Chris King has been invited to present his work at the following:

WOMEX interviews Christopher King

Le Guess Who? Festival in Utrecht

The Megaron Mousikis in Athens

Paris Review

New York Public Library

Bucknell University, Department of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies

Library of Congress, Packard Campus

Gennadius Library of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Society for the Preservation of the Greek Heritage

Greek Institute of Cambridge, Massachusetts

National Hellenic Museum

Athens Conservatoire (Odeon Athinon)

Pallini School of Music

Silversmithing Museum of Ioannina (Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation)

Under Cover: In Pursuit of an Unearthly Record

What inspires a music collector to search high and low and pay large sums of money to acquire one record? Obsessiveness, says Chris King, who owns the record “Last Kind Word Blues,” by Geeshie Wiley, that appears on this week’s cover.

King’s record is one of fewer than 10 surviving copies of the three known Paramount releases from Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas, the mysterious blues musicians who are central to John Jeremiah Sullivan’s cover story. “People in the story talked about this record as being the holy grail of blues collecting,” says Amy Kellner, a photo editor at the magazine, so it made sense to show “one of the only physical clues to these two women.”

Here King talks about his music collecting.

How did you acquire your copy of “Last Kind Word Blues?”

I had to work very hard for several months. I acquired the disc out of a trade with another collector. At first, I got him to bring the record to my house, where I listened to it. And then I started to make him offers, which were preposterous at that time.

But the second time he came to the house with that record, he had learned that I had recently turned up a very rare record. This time I approached him with a nice stack of money, a stack of records and that rare record, and he accepted because he didn’t actually believe I would go through such lengths to acquire something. And that’s how I got it.

Why were you willing to give so much for this one record?

Have you ever heard the record? This record is the tip-top, pinnacle of that genre of records that shouldn’t exist because they are so unearthly. When I sit in my studio and play this record, it has so much vibrancy and life to it, that when I drop the needle on it, I half expect for blood to flow from the grooves or a tear to drop from the turntable.

After I heard that record long ago, I said to myself, “I will do whatever it takes to acquire it.”

Before reading John Sullivan’s story, did you know anything about Geeshie Wiley?

Because the slate is so blank when it comes to these two women, collectors, just like anybody else, have this urge to mythologize. For me, having listened to “Last Kind Word Blues” and “Skinny Legs Blues” — in my mind I picture this cold, hardened, glaring, gray-eyed woman; a femme fatale who would slash your throat just as soon as she would make love to you the next instant.

I know John [Sullivan] has probably pulled up a lot more information about them, but in my mind, I see an extraordinarily strong, independent woman.

Why did you begin collecting old records?

My dad was a big-time collector. He makes me look like a puny ant. He collected everything — phonographs and film and antiques and art. So I had that natural proclivity to surround myself with objects. It was a natural transition.

Why records, then? You have more than 5,000 of them.

It sustains me. It gives everything meaning. If I was not able to both collect and make material available to others, I don’t think I would be able to find the universe coherent. I don’t think I would be able to find any meaning to anything.

What's Your Story? Huffington Post Interiews Chris King

Huffington Post What's Your Story

So, Chris, what's your story?

I'm an auricular raconteur and sonic archeologist. I listen to old 78s that were recorded before our parents were born, and these old records speak to me sometimes. My job is to midwife their voice, stitch them up in a new suit of flesh and offer it as nourishment. According to you, I also cook. That sounds similar.

You are my favorite cook who does not work in a restaurant. Will you mention two or three favorite go-to cookbooks? I love the cookbook from The Grit, in Athens, GA. and The Joy of Cooking.

I mainly depend up recipes that are found in the book of Revelations with ingredients sourced from the book of Leviticus. Occasionally I'll refer to some of Rilke's pastry recipes.

Tell me about your latest compilation, which features the music of Alexis Zoumbas.

I developed an idée fixe with Albanian and Epirote music after junking some old 78s of this music in Istanbul a few years ago while on vacation with my wife and daughter. This (un)naturally lead to an obsession with many of the artists from this region that played this style of music which is frankly more powerful, unvarnished, and "heavy" than any other music I've yet to encounter. In fact, it is so unpretentious and stark that I doubt that many would even regard it as music... it is more like a profound tonic or salve for our wilted spiritual wounds. I noticed that while I got deeper into this harmonious language. one artist, Alexis Zoumbas, proffered something in his music that was subtly distinct from many of the others. My inquiry into what this difference was led me to acquire almost all of his 78s (there were about three dozen solo violin recordings that he made from 1925 to 1930), travel to Southern Albania and Northern Greece to interview his surviving family (he died in 1946), and essentially reconstruct a narrative of a man whose life was largely mythologized and erroneously represented. The music of Zoumbas is meant to enrich us all or at least to offer some succor.

I recently had some success with smoking a turkey at Christmas and a pig on New Year's Day. You do a lot of grilling and smoking... would you care to offer any tips?

I love to grill as it reconnects me with my Scotch-Irish-Neanderthal ancestry. The only tip I can offer is "Fire is good." It is also the case that I avoid grilling and smoking the more "innocent" of the meats... only the old, infirm, and more experienced animals should be prepared in this manner.

What do you especially like to cook? I know chicken and chorizo shows up on the King menu quite often.

As indicated above, I have a particularly fondness for the "innocent" meats... veal, spring lamb, suckling pig... something that really hasn't developed a memory.

Any ingredient can be bettered by cooking it with pork since swine have a great deal of intelligence and obviously, memory. So, cooking a suckling animal in a porcine substrate is like surrounding innocence with experience... a Bergmann entree or a Bruno Schulz appetizer?

The renowned drummer Clyde Stubblefield once equated drumming to cooking: "Sometimes you gotta slow cook some stuff over here, and sizzle fry some stuff back there..." Do you draw any correlation between music (or art, in general) to cooking?

I see no relation between drumming and music.

You compile music from many diverse geographic areas (Louisiana, Virginia, Greece, Albania)... is there a musicological frontier out there that you look forward to exploring?

The thread that runs through the music I collect and explore is rural and raw in nature and so I'm hoping to weave myself up through the Balkans into Macedonia and into Anatolia. For some reason I'm drawn to musicians born in the 1880s.

What are some things you don't like to do in the kitchen? What are some of your favorite things to do?

I fucking hate to do dishes.

My favorite thing to do is the "fine-tuning nervous hovering," the addition of ingredients 30 seconds or so before the meal is served. With Thai food this is the adding of the fish sauce, in Greek food it is the adding of lemon juice, in mid-Western cuisine (especially from Cleveland) it is the adding of anything to overwhelm the blandness (this, of course, does nothing).

Who do you cite as big inspirations -- in or out of the kitchen? Why and how?

John of Patmos, especially Revelation 3:16:

"So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth."

Who are some of your favorite boundary-pushers -- in food, music or anything else?

My favorite "boundary-pusher" is Andrei Tarkovsky. Not only did he have an infinite (and justified) self-confidence but he had a vision that could only be regarded as "spiritual." His determination and his accomplishments came from a strictly followed set of rituals that prepared him for his day's work, his week's work, his year's work. The guy fasted before starting a film and maintained a focus and obsession until the film was done. He staunchly protected the integrity of his work. A while back someone said: "Facebook! It makes being a friend easier!" Tarkovsky, if he were alive, would have replied "Friendship is not supposed to be easy. That is the problem... everything is too easy nowadays. Things should be hard. Friendship should take effort and care. Go paint an ikon and then tell me that ikons make religion easier."

Please tell me about your upcoming trip to Greece this summer.

The trip to Epirus/Albania is the result of being awarded a Cultural Exchange Grant from the Mellon Foundation and APAP under the auspices of the National Council For Traditional Arts. I am planning on returning to Epirus (Northern Greece) and Albania this August where I will be recording, interviewing and documenting Roma musicians that perform at feast-dances in Greece and Albania. I also hope to research the sublime clarinet player, Kitsos Harisiadis, who recorded in the earlier part of the 20th century. I also intend to consume many lamb entrails.

Talk to me about books: who are some of your favorite writers? Will you please name three of your favorite books?

In no particular order: Bruno Schulz, Franz Kafka, Patrick Fermor, Amanda Petrusich, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Gary Shteyngart, Jim Potts, Stanislaw Lem, Flannery O'Connor, Fydor Dostoevsky, William Burroughs, Ishmael Reed, Ismail Kadare, Albert Camus. It is difficult to name just three of my favorite books but likely for pure pleasure: Roadside Picnic, Street of Crocodiles, and Mumbo Jumbo.

You're not a big dessert eater... what's your favorite meal-ending dish, besides whiskey?

I am intolerant of sweets but I greatly enjoy a little Beaufort D'ete to close a meal.

Thank you, Chris. Do you want to provide me with a verb for that last sentence? And would you entertain one more question? What are some of your favorite musical groups and records?

Sorry..."relish."

How about: ODB (RIP) and Alexis' Zoumbas' Epirotiko Mirologi

ODB (Ol' Dirty Bastard) is a little tongue-in-cheek, or no? He's post-1930s rap. As opposed to pre-...

I LOVE Shimmy Shimmy Ya.

Chris's newest project will be released on Record Store Day, out on Angry Mom Records.

Chris and Stuart in the kitchen...

Video: The 78 Project on the Road: Christopher King plays Geeshie Wiley "Last Kind Words Blues"

The 78 Project on the Road: Christopher King plays Geeshie Wiley "Last Kind Words Blues"

Shot on the road in Virginia, August 24, 2012

Producers: Lavinia Jones Wright & Alex Steyermark

Director, Editor, Camera: Alex Steyermark

Sound Recordist: Lavinia Jones Wright

The Recorder 10.24.1974 Les King's Musical Museum... A Fascinating Collection

Chris and Les King

The Recorder 10.24.1974 Les King's Musical Museum... A Fascinating Collection

ISSUE 79: Amédé Ardoin—Accordion Virtuoso

Published on November 29 2012, Oxford American Magazine

DRAGGED THROUGH THE FOREST: The Long-Gone Sound of Amédé

Music critic Amanda Petrusich is the author of several books, including IT STILL MOVES: LOST SONGS, LOST HIGHWAYS, AND THE SEARCH FOR THE NEXT AMERICAN MUSIC.

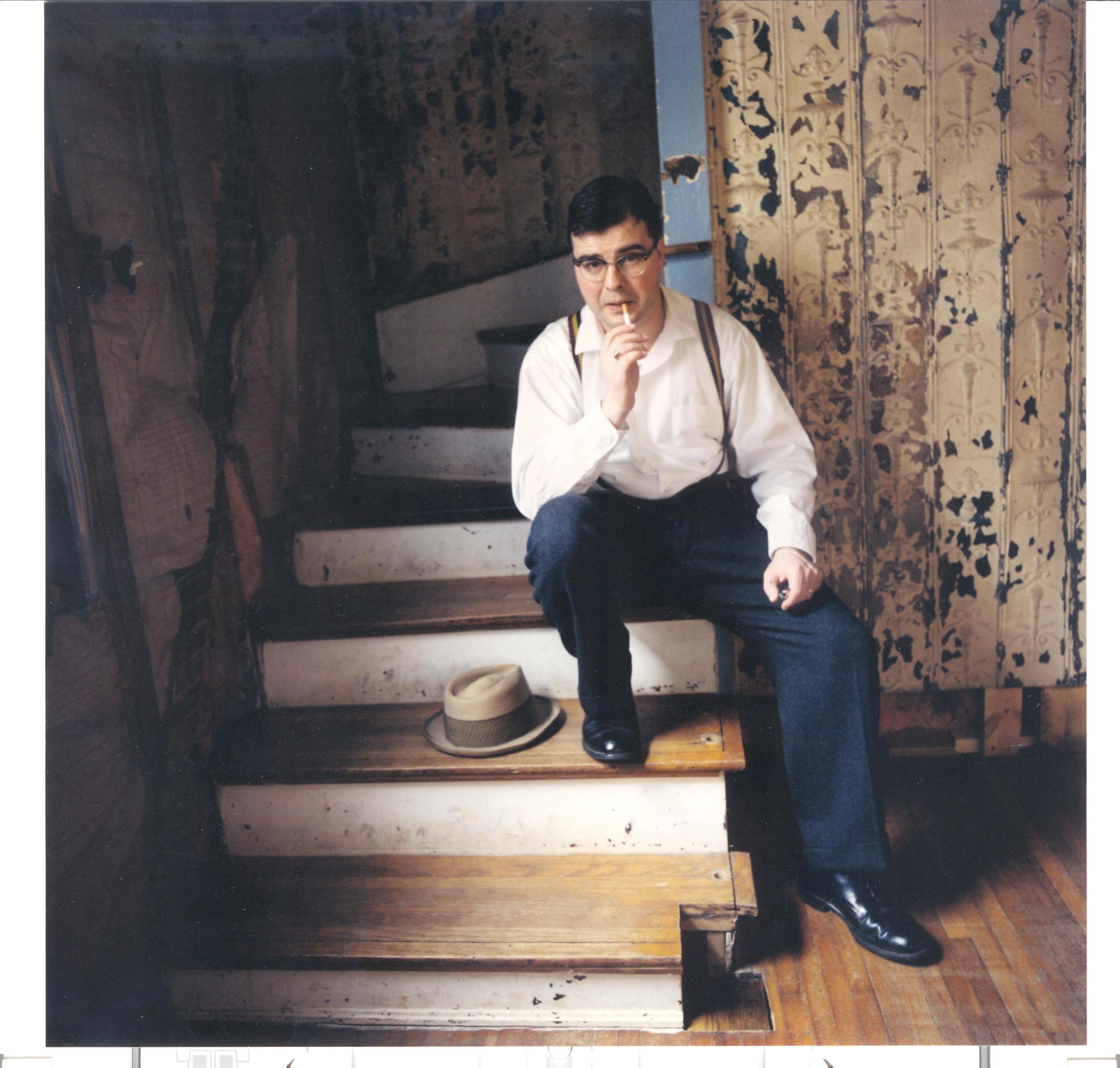

I first met Christopher King in central Virginia, in August 2011, the same afternoon Hurricane Irene came whipping through the area. I’d been referred to him for help with a project about collectors of rare 78-rpm records, and I spent most of the drive to his home dodging cracked branches and other tree-borne detritus, eventually parking my rental car in a giant puddle and booking it to his doorstep. The man I met at the door had short, dark hair that he combed back and to the side, and a pale, round face that suggested a certain kind of old-fashioned innocence, although in actuality he was sharp and acerbic, quick with an eye roll and unlikely to let you get away with saying anything stupid. He was an easy person to talk records with: precise but open-minded, which was good, because he spent much of the next year, on and off the telephone, patiently walking me through the nuances of various recorded phenomena.

King works most days as a production coordinator at Rebel Records, a bluegrass label, and County Records, an old-time label, both based in Charlottesville, but he is also the owner of Long Gone Sound Productions, a sound engineering and historical-music production company. On his office desk, alongside a big outmoded computer, there’s a green Remington typewriter. His eyeglasses are from another era. He doesn’t own a mobile phone and referred to mine as a “smart-thing.” His house in rural Faber, which he shares with his wife and daughter, is outfitted with an assortment of carefully vetted antiques and oddities. Like many collectors, King has insulated himself from the facets of modernity he finds most distasteful. During one of our conversations, he asked me if Lady Gaga was, indeed, “a lady.” He was not being coy or funny. He is forty-one years old.

In the winter of 2010, King masterminded the release of Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone, the complete recorded works of the black Cajun accordionist Amédé Ardoin, who is recognized today as a forefather of the genre. It was the first installment in King’s “Long Gone Sound Series,” for the Tompkins Square label, and is still the only comprehensive collection of Ardoin’s music ever issued.

Amédé Ardoin was born in the spring of 1898, the grandson of slaves. His family worked as sharecroppers at the Rougeau farm in L’Anse des Rougeau, near Basile, Louisiana. Ardoin tried his best to avoid field labor whenever possible, preferring to tote his Monarch accordion to house parties, where he’d team up with like-minded fiddlers and play early iterations of the frenzied dance songs that would eventually constitute the Cajun canon. The music is, above all, a physical incitement, a call to the floor: two-steps and one-steps and waltzes, songs to move to and be moved by. Between 1929 and 1934, Ardoin recorded seventeen two-sided 78-rpm records for a handful of labels, all of which King has gathered, studied, and sequenced over two compact discs. King also produced, notated, and re-mastered the set himself, and nearly all the source 78s were plucked from his private collection, itself a vast and staggering thing. Why is Ardoin so important to King? “I just naturally, intensely, obsessively gravitate toward music that is emotionally unhinged.”

In the liner notes for Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone, King writes that Ardoin “left us a legacy that, in at least two respects, shouldn’t exist.” The first of those concerns scarcity: Prewar 78s are a finite resource, and the discovery and acquisition of playable Cajun records from the 1920s and ’30s is a near-farcical pursuit. Records, collectors will tell you, have a way of hiding, and it’s not inconceivable that any number of Ardoin’s sides could have stayed buried, decomposing at the bottom of a mottled cardboard box in some clammy bayou basement. As it stands, there are only one to three extant copies of most of Ardoin’s 78s, all in varying states of decay.

In the late 1990s, after King heard his first Ardoin 78, at the collector Joe Bussard’s house, he methodically set about trying to acquire all seventeen records, a process that remains somewhat mysterious to me but seems to have involved a lot of heated late-night phone calls and swashbuckling trips into barns. Ardoin’s 78s have to be finessed into possession. They rarely appear at auction, and convincing a collector to sell or trade one involves a complex psychological and economic algorithm that boils down to figuring out what someone wants more than the record you’re trying to acquire, and getting your paws on that, often by repeating the process with yet another collector.

The other reason Ardoin’s music ought not exist, according to King, is a little more complicated, having to do with Ardoin himself, or, more specifically, with his singing voice, which in his notes King calls “seemingly not of this world.” One might be tempted, now, to cite a cornucopia of high, spectral American yelps—from Skip James to John Jacob Niles to Axl Rose—as analogues or even descendants, but Ardoin’s vocals are singular in their unearthliness. If you listen to Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone for any extended period of time, Ardoin’s voice (feral, galloping, deranged) starts to seem like a self-obliterating force. That it sustained him—that, in 1929, a person could saunter up to a fais do-do, swing open a door, and encounter it—is what King finds astonishing. I understand why: The first time you hear Ardoin wail, the sound demands a reckoning, an acknowledgement that maybe you don’t know everything you thought you knew, and, in fact, maybe you don’t know anything at all.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Musicians recognize that there is both a discovery and an abandonment of self that can occur onstage; when Ardoin sings, the self that emerges feels like a manifestation of the collective unconscious, like I am singing and you are singing and everyone we know is singing, but there’s no supreme harmony to conceal all our mess and yearning. It seems worth noting that I have no idea what Ardoin is talking about most of the time, at least not in the literal sense. I don’t speak the language (King describes it as “Cajun French speckled with Creole idioms”), and the handwritten transcriptions King offered up at my request seemed nearly incidental separated from the music, like an epic meal reduced to its ingredients list.

What King told me is that it’s possible most of Ardoin’s songs are about one person: the girl to whom he was betrothed, or about to be betrothed—the most profound romantic fascination of his young life. As far as I can tell, theirs was a shotgun-to-the-temple, unbearable, drive-it-like-it’s-stolen love, uncompromising and insane. Something went wrong. They never married. According to “Valse Des Opelousas,” she left, crying. “Oh, tite fille, si tu m’aimerais comme t’as voulu me dire / Tu te sentirais pas déçue pour ça ils sont après te dire,” Ardoin sings after her. Oh, little girl, if you loved me as much as you said, you wouldn’t feel so disappointed by what they’re telling you.

“In my understanding of that culture, in that particular time period, because it was so intensely Catholic and superstitious, you got married, and you didn’t get a new wife or husband until the other one died,” King explained. “The same stigma was attached to betrothal.” Ardoin’s romantic outlook, from then on, was grim. The way King figured it, “There was a woman for you, and if you didn’t get that one, well, you know, you were just fucked.”

Because he couldn’t have her, Ardoin sang to her, over and over again. She appears often as “Jouline,” which King suspects was a pet name, a variation of “jolie,” or “pretty young thing,” though her actual name was Maisé Broussard. I imagine her as the kind of beautiful that makes your stomach hurt: sweet-faced and long-legged and a little mischievous around the eyes, too smart for her own good. King likes to think that Ardoin sang to her with the hope that she’d eventually hear his prayers and adjurations—that he believed he could, in effect, sing her back to his side. He was clearly ready to die trying. “Oh, tite fille, moi, j’ai dit je m’aurais jamais marié / Oh, c’est rapport de voir ça t’as fait avec moi,” he sighs at the end of “Valse Des Opelousas,” his body gutted, his voice tired. Oh, little girl, I said I would never marry. Oh, it’s because of seeing what you’ve done to me.

There is something both freeing (there is only one right choice) and terrifying (there is only one right choice) about Ardoin’s insistence upon Broussard, and whether that focus was culturally mandated or a personal imperative seems irrelevant. It doesn’t matter if Maisé Broussard heard these songs, or if she knew what Ardoin wanted. She was gone. She married someone else, and in her absence Ardoin became fundamentally, existentially unmoored. I’m certain this is the most brutal kind of loneliness.

“When I started to listen to Amédé Ardoin, I noticed this repeating pattern, these mentions of house and home: ‘I have no house to go to,’ ‘I have no home to go to,’” King told me. Indeed, Ardoin constantly equates heartbreak with being disowned, with being robbed of tenderness, and with being orphaned, and thus he reaffirms the clichés about loss fueling art, or loss necessitating art. “I would have to say, the obsession with this one woman—if indeed this narrative is true, and, as with a lot of narratives, I would like to believe it’s true; it makes it more romantic, more compelling—is what makes his music vastly more intense than practically any other Cajun performer from that time period,” King said. “Because when you listen to him alongside accordionists who were recording more or less during the same time period, they all play very nice accordion, and their delivery is tinged with emotion. But Ardoin’s has that little bit of extra hellishness to it.”

What King is too diplomatic to say is that eventually almost everything else sounds bloodless next to Ardoin. Anyone who has lost something will hear part of his or her hurt echoed back when Ardoin sings, but it’s a satisfying, transformative pain, like getting a tattoo or saying a particular kind of goodbye. When I asked King what he experienced the first time he heard Ardoin’s music, he didn’t equivocate. “It was like being grabbed by the neck and then being smacked around, and then being dragged through the forest,” he remembered. “But it was all seemingly pleasurable.”

Given that Ardoin’s recordings were intended for an isolated and indigent population—the two hundred thousand or so Cajuns and Creoles living in southwest Louisiana—who likely still thought of music as a thing to be encountered live, and not as an unwieldy black disc you brought back to your parlor and watched spin, it seems remarkable that they exist at all. “When you think about southwest Louisiana broadly, you’ve got the lake areas, the marshes, but principally you’ve got the Lafayette region, which is basically one hundred miles around. That happens to have also been the place where Ardoin played,” King said. “Why the hell would you go buy something when you could see it, participate in it?”

In his notes, King writes of how an American musical canon lacking Ardoin might have created a kind of “aesthetic starvation.” I was thinking about that late one summer night, after we’d both been drinking, and I told King I got the sense that the chain of events leading to the creation and dissemination of Ardoin’s records was somehow preordained and necessary. I was talking through the bourbon, but King and I had gotten into this kind of thing once before, on an early-morning drive to a flea market in Hillsville, Virginia, where King was junking 78s and I was taking notes. Back then, he’d suggested it was possible certain changes in the way we created and consumed music had directly contributed to a plague of cultural and personal degeneracy—that we required music like Ardoin’s, with its honesty and insistence upon itself, to help maintain our humanity. I think what he actually said was: “What the fuck happened to music?”

Later, on the phone, he clarified: “When you’re deprived of stuff this raw and yet so integrally tied to what a person ought to be, to where they came from—if you cut that away, if you amputate it, if you deny it, then you have an aesthetic starvation that leads to a starvation of other parts of the person.”

I’ve since spent a lot of time pestering King to isolate precisely what it is about Ardoin (and all the music he loves and collects, from Albanian folk songs to rural American ballads) that he can’t find elsewhere. I’m not sure what I want him to say. It’s possible I’m asking him to clarify my own relationship to the material, to tell me why it matters to me so that I can better manage what it makes me feel. He will admit only that unselfconsciousness—freedom, as he says, from the “insane lust to assimilate with this bland culture”—is paramount. “It seems like in the teens and ’20s and ’30s, there was a much, much stronger resistance to cultural assimilation. The first generation of immigrants, or people that lived in isolated, idiosyncratic pockets of the United States, knew their thing and they played their thing all the time and then that thing became second nature,” he has speculated. “So maybe that’s what makes it so uniquely compelling and powerful and overwhelming at the same time. These people are really fucking comfortable in their own skins, and I don’t think that you can say that about rock stars nowadays.”

Eventually, he always gives up, summarizing the essential paradox of Ardoin’s recordings like this: “Ultimately, they really shouldn’t exist. They’re just too beautiful.”

Collectors of 78s inhabit a curious role in the history of American music. They are gatekeepers by default, often the only men (and they are almost always men) with access to certain songs. King is generous with his bounty. Score an invitation to his house and he will play you almost anything you want to hear. The sets he curates are heartfelt, coherent things, as much an expression of King’s beliefs and point of view as the artists. “When I do these collections, there are things that are both intentional and unintentional in the background, that are lurking back there,” he admitted. Those narratives are conspicuous, even on Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone. Often, for King, they have to do with irrational longing, with what he defines, in the liner notes to Aimer et Perdre, the collection of prewar love and loss songs he recently produced, as “our inexplicable mulishness in seeking out relationships that we know will ultimately both enrich us and devastate us, more often at the same time.”

As fervent and dedicated as he is to collecting, King’s proficiency as a sound engineer is nearly unparalleled (he will cite Richard Nevins of Yazoo Records as his better), and while his collecting lets him get closer to Ardoin, it’s the re-mastering that allows him to actively participate in a song, becoming a part of the sound and, consequently, its legacy. Most of the source 78s on Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone were file copies, meaning they’d never been played before, but the more battered 78s necessitated a bit of mindful tinkering. “The thing I was going for, to put it in Rich Nevins’s words, was not to ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater,’ but rather to demonstrate the vitality and the dynamics that were originally apparent within the studio when the actual recording took place, when the performance was made,” he told me. “By doing so, you’re necessarily going to get more noise. That’s just part of the spectrum, part of the frequency that you capture.”

King, for his part, hears things that other people don’t hear. He is capable of conjuring and magnifying tiny secrets—a foot-stomp, a person singing along from a different room—from records that, to modern ears, already sound preposterous. For example, one evening he told me to listen very carefully to “La Valse à Austin Ardoin.” “When the accordion break occurs between the vocals, you can hear him humming—like a Glenn Gould–type sound,” he said. Later, when I slipped the CD into my stereo and curled up near the speakers, I thought I caught it, about a minute in: Amédé Ardoin giddily humming along with himself, doubling the melody, goading it forward. For a second, Ardoin felt familiar to me, like I could finally understand his breath, the origin of his voice. But when I listened again, it was gone: a phantom. The feeling of loss was palpable, similar to the several-second delay between waking up from a magnificent, life-affirming dream and realizing that you’re going to have to use a folded paper towel as a coffee filter again, and also it’s raining. I emailed King. How had I lost it? How did he know it was a hum? How did he know it wasn’t just air escaping from the bellows?

He’d thought about it. “The main reason why I can differentiate it from the bellows is that on the diatonic accordion in D, you have to switch the push/pulls in order to play a natural progression of notes; to wit, to play the three natural notes D–E–F#, you will have to push on the D (third button, first position), pull on the E (third button, first position), and push on the F# (fourth button, first position). However, if you are playing a melodic line that depends on a long pull or a long push on the bellows (which is what Ardoin is doing, particularly when he plays strings of triplets), you are not going to hear any non-musical information (air from bellows) because the direction is not switched. Also, if you could hear air blowing out from the bellows, then your accordion would need some repair (a hole in the bellows for instance or a leaky reed or stop), and Ardoin would have fixed that or had it fixed prior to recording,” he wrote back. “Also, I can hear it, can’t you?”

I understood it was a thing we both needed. But I couldn’t. I don’t.

Although Ardoin played with many fiddlers in his lifetime, including the incomparable Douglas Bellard, his most enduring creative partnership was with Dennis McGee, an orphaned white sharecropper from Eunice, Louisiana, who is credited on twenty of Ardoin’s thirty-four sides. Such interracial alliances weren’t unprecedented, but it’s likely the relationship was socially fraught. McGee probably recommended Ardoin to Columbia Records, which would make him ultimately responsible for Ardoin existing outside of his time and place. McGee himself had probably been suggested to the label by the pioneering guitar and accordion duo Joe and Cléoma Falcon. Back then, recording artists were recruited almost exclusively by word of mouth.

There is a mystical quality to McGee and Ardoin’s dynamic, a seemingly fated synchronicity. “They’re driving each other,” King said of it. “They’re pushing each other forward. McGee’s fiddle is edging Ardoin to play better, and Ardoin’s playing is edging McGee to play better. To me, it’s one of those rare instances in the whole phenomenon of musical performance where two people make each other perfect.” McGee and Ardoin met as kids, when they were working on the same farm. According to King, they may have started to play together when Ardoin was just ten or twelve years old. As adults, they shared a sense of alienation, of rootlessness. “McGee’s mother died, and McGee’s father really couldn’t take care of him, and so he sent him to live with some relations,” King explained. “The relations really disliked McGee. And McGee disliked his relations.”

In 1983, a ninety-year-old McGee, being interviewed by Alan Lomax for Lomax’sAmerican Patchwork series on PBS, spoke gently of his former partner. “He could make people cry when he sing, oh boy, he was a good singer,” McGee said, nodding, his voice soft. I can only imagine what Ardoin would have said of McGee, who is now widely considered a progenitor of prewar Cajun music, a fierce and intensely mesmerizing player, a savant. On that same trip, Lomax shot video footage of McGee sitting on the front porch of his home in Eunice, playing “Adieu Rosa” while one of those grand, sky-bruising Louisiana thunderstorms lumbered past. McGee died six years later, in 1989. The performance is still a startling thing to behold: His head is thrust back and the rest of his body moves jerkily, like a zombie’s; he blindly stomps a loafer on worn porch boards. McGee doesn’t seem entirely present when he plays, and I envy him that solace. Wherever he goes, it seems quiet, insulated. What it yields for the rest of us—waiting out here—is staggering.

The story of Amédé Ardoin’s death is apocryphal, something he shares with the Delta blues singers Robert Johnson and Charley Patton. Sometimes mythology supersedes fact for so long that it becomes its own kind of truth by virtue of our belief in it; or, as with Ardoin, the details vary but the arc stays the same, stays true. Here’s what we think we know, based on firsthand accounts collected decades later: Ardoin was playing a party, when the white daughter of the house either lent him her handkerchief to wipe his face, or went so far as to mop the sweat from his nose herself. A group of men who King believes were from out of town—Virginia, or maybe north Louisiana—were so deeply appalled by the gesture that they surrounded and attacked Ardoin when he tried to leave, or they ran him over repeatedly with a Model A Ford before kicking his limp body into a ditch, or both. Whatever happened, Ardoin didn’t die, not right then—not in the medical sense. Friends and witnesses described him as “damaged.” His vocal cords were minced, and he began, as King writes, “a slow descent into solipsism and silence, a sudden loss of comprehension, and an inability to play and sing.” Not long after, on September 26, 1942, he was institutionalized, sent off to an asylum in Pineville, Louisiana, where he died less than six weeks later and was buried in a common grave. In one story, which King cites in his notes, Ardoin was spotted briefly outside of the asylum, hoofing it back to Acadiana, still looking, I like to think, for Maisé Broussard.

In Virginia: The Collector, Oxford American Issue 45 →

Even among the eccentrics who hunt for rare 78 records, Chris King stands out.

Chris King lives in a nineteenth-century farmhouse in the foothills of the Blue Ridge, not far from the real-life Walton’s Mountain made famous by television. Until now he’s been a gracious host, providing sweetened iced tea and breaded chicken livers and playing records from his vast collection of vintage blues and hillbilly 78s. But I’ve made the mistake of asking him if he digs Howlin’ Wolf, and he’s clearly offended, as if I’ve just spit on the hardwood floor of his immaculate record room. My assumption that he’s a fan of Wolf, one of the greats of the post-war blues era, is an assault on King’s finely tuned sensibilities.

“That’s way too slick,” he says.

It’s an outlandish description of Wolf, who by any reckoning was more akin to a force of nature than a polished entertainer. (“This is where the soul of man never dies,” said producer Sam Phillips when he heard Wolf sing at his first Sun session.) And now here’s King dismissing him with cool arrogance. It’s not like he’s calling Howlin’ Wolf a pantywaist— still, I can’t let it slide.

But King isn’t one to chase down a confrontation, even with someone who’s challenged one of his pronouncements. He’s mild-mannered, a formal sort who “yessirs” his elders and strangers, a country boy raised the old-fashioned way. It’s no surprise to learn that after college he worked for a year at a funeral home, a job he may have pursued as a career if not for the irregular hours. (He says he got some fine records from estate sales at the homes of many of the deceased.) So instead of pushing or biting back, in his defense he turns to the arsenal he keeps at the ready for such situations: roughly a thousand shellac 78s nestled in custom-made shelves of sturdy poplar. He pulls out a record, forgetting his usual decorum: “Now this, this is fucking raw.”

King puts the record on a turntable, part of a vintage hi-fi system that is one of the few concessions to modern technology in a house crammed with Depression-era appliances and artifacts. It is “Rising Sun Blues” by King David’s Jug Band, a black group recorded in Atlanta in 1930. The music kicks from the speakers: a guitar and a mandolin nudging each other along, two jugs laying down a bottom rhythm, and a singer weaving his way through the syncopated bramble.

I got twelve little puppies

And ten big shaggy hounds.

It takes all of those doggies

To run my brown skin down.

King listens with reverence, and shouts over the din: “Have you ever heard a voice like that? That’s one-hundred-percent pure backwoods rural shit!”

When the record ends, he gives a brief history: It is one of only a handful of copies, a clean one he junked in a box of hillbilly 78s at a West Virginia flea market. The group made only three records, all highly sought after by collectors. Little is known about the band members except tidbits gleaned from lyrics; King figures they probably hailed from somewhere near the Alabama–Mississippi border.

“That voice is so separated from anything that you could ever hear nowadays,” he says. “It’s like from a lost colony: There’s no way that anybody could affect that voice, let alone have it nowadays. It’s a voice from somebody from some obscure town who probably never went to school beyond the fifth or sixth grade, and probably talked like his parents, who talked like his grandparents. It’s a purely historical, regional voice that can never be duplicated. It’s totally unique.”

For King, this lost voice is a clue to how pre-war blues and country have cast their spell on him. It carries the weight of centuries in its sound, and bears the traditions of countless pockets of isolated, homegrown cultures wiped out by the spread of radio and, ironically enough, records. As performers throughout the South began to emulate the quality and effect of records, they sacrificed their own idiosyncratic styles, making way for the amplified, homogenized music he despises, which, besides bluegrass, includes pretty much everything recorded after World War II.

There are plenty of collectors whose shelves have a place for Howlin’ Wolf next to pioneers like Charley Patton and Charlie Poole, but King is not your average 78-record fiend. At thirty-one, he is a youngster among geezers. Most collectors, like R. Crumb, came of age in the ’50s, rejecting their parents’ big-band records and the rock & roll favored by their teen peers.

King’s love of ’20s and ’30s music, however, is part of a family tradition: His father, Les, was one of the early collectors of hillbilly records in an era when this music was held in low regard by nearly everyone outside the communities that had spawned it. A music teacher by trade, Les King was a repairman, too. He took both skills on the road, traveling throughout Bath County near the West Virginia line to give private lessons and do odd jobs, often in exchange for objects that struck his fancy. “My dad was probably the most inveterate collector you could imagine,” says Chris. “He had one room with nothing but phonographs, another for music boxes. The basement you couldn’t even walk through, it was so full of stuff he’d picked up. He was a shameless seeker of anything. He’d go into a house and see something and say, ‘You have any more like that?’ and pretty soon, instead of teaching the kid, he’d be in the basement looking for stuff.” Victrolas were Les King’s main interest, and with each of these phonographs often came a batch of 78s, eventually numbering more than twenty thousand. The sheer bulk of records ultimately overwhelmed him, and without the space or time to deal with it, he sold his collection when Chris was still just a boy. (The music boxes and Victrolas are at the home of King’s mother.)

Starting out with nothing, King has not only found a way to make 78s a recovered family tradition, he’s gone a step further by making the records available in a way his late father could never have foreseen. For County Records, King has produced scads of compilations of old-time music for a whole new audience. As a restoration engineer, he makes analog-to-digital transfers of 78s that render the nearly century-old recordings accessible to modern ears. His work on Revenant’s seven-CD Charley Patton box set,Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues, earned him a Grammy.

“Chris has the knowledge, he has the ear, he has the equipment and the technique,” says Marshall Wyatt of Old Hat, a North Carolina–based label, who worked with King on a compilation of black fiddlers from the ’20s and ’30s. “But he’s more than a technician, he’s an aficionado, a lover of the music. It’s not just, Bring me a stack of records and I’ll transfer ’em, it’s, Let me help you find the very best copies.”

Even for a fan of the music, this is painstaking work. Many of the most prized blues and country 78s survive only in the most wretched condition, gouged as they are by the steel needles of the old Victrolas. For the Patton project, King transferred over a hundred sides, mostly Paramounts, which are notorious for their inferior pressing and beat-to-hell copies; he managed to salvage crisp, clear transfers from all but the most battered copies. “There are spots in the groove that, for whatever reason, haven’t been tapped,” says Dean Blackwood of Revenant. “If you view it as a relief map, part of the terrain hasn’t been traveled on and Chris can get to it. He knows where to go in the groove to find music that’s still coded in there, that hasn’t been ground down to nothing.”

The entire operation, which King calls Long Gone Sound, is crammed in a tiny record room: a fancy pre-amplifier and soundboard mixer, a pair of ’50s-era tube amps on milk crates, and some high-end speakers that can rake the wattage King pushes through them. He likes to play these records loud. He has a few dozen styli that he uses to eke out some half-buried fiddle break from a worn shellac groove. Dropping the needle on an old 78, again and again and again. He calls this meticulous process “cracking the code.” What might seem tedious is for him an intricate communion. “It’s all in the whole ritual. As naive as it sounds, when I play a 78 on my turntable, it makes me feel closer to the music than playing it on a CD. It takes a special breed—there’s only so many weird, whacked-out eccentrics who get a big kick out of that three-minute experience.”

There’s a framed photo of the Skillet Lickers, the Georgia hillbilly band whose raucous fiddle tune “Liberty” was the first 78 that peaked his interest in old-time music.

But the place of honor, above his corner workspace, is reserved for a ’40s-era girlie poster by cult pin-up artist Gil Elvgren, one that predates his later nude studies. This is part of King’s pre-mass-media aesthetic. “The best thing about early Elvgren is that he gives you just enough leg for you to imagine what’s right above it,” he says.

King and his wife, Charmagne, have spent more than a year renovating their 130-year-old house, a project nowhere near completion. He recently stripped the walls of the room where the previous owner shot himself. The house is filled with period pieces salvaged from junk shops and estate sales, from a 1932 toilet and claw-footed tub to an antique pie safe and 1938 Hot-point electric stove, of which the hazardous open heat coils don’t bother King a whit. “It’s gorgeous,” he says. “It’s like a work of art. I got it out of my granddad’s basement. For us, the classic style is late Deco and early rural poverty. Most modern stuff is shit. It’s a throwaway culture. You buy a chainsaw, and after a year you throw it away and buy another one.”

King’s grandfather was an old-time fiddler who never recorded professionally. For King, he represents the pool of grass-roots artistry of the highest order, only a fraction of which was captured for posterity. “In the ’20s and ’30s, and way before that, there is no measure of the incredible musical talent that was around, both recorded and unrecorded. Now, what the hell is there? American Idol?”

Nothing gets King as riled up as talk of the modern world versus the workaday one of his grandparents. To his thinking, even the Depression is somewhat sullied by progress. His ideal is sometime around 1870, when his house was built, and life moved at the easy pace of a horse’s trot, and songs were still handed down. This era was the heyday of what King calls “true vine” music, made by obscure performers whose repertoire dated back before the blues to murky, racially mongrel nineteenth-century origins, when blacks and whites in the South not only shared the same grab bag of songs, but often the same local styles. The 78s he covets capture spontaneous, raw performances, when the only prodding from record-industry engineers was a bottle of whiskey and some pocket cash: Texas songster Henry Thomas, whose music can be heard on TV commercials via Canned Heat covers; Kentucky fiddler Jilson Setters, who made records well into his seventies; the black duo Two Poor Boys, whose songbook stretched back to the Civil War. “True vine is music that’s not shaped or molded by crass commercialism,” he says. “It’s the stuff that would have been in the American vernacular before there were phonographs or music marketeers. They didn’t have someone telling them what to do, they were playing the way they’d always played.”

There are a few dozen records that have this elusive quality, and King is always on the lookout for more. “The most captivating performances, the ones I absolutely have to own, are the most backwoodsy, informal recordings that you can’t possibly imagine. To me, there’s no such thing as a dichotomy between black and white, between blues and hillbilly. It’s more like a dichotomy between country and city. There’s the stuff that was made to sound slick, like they were recording for the microphone, versus the stuff in a country setting, where it’s like the person walked into the room and did what they did every day of their life. It may sound weird and alienating to us, but that’s because it was second nature to them.” An example of this “purely American rural music,” he says, is “That’s My Rabbit, My Dog Caught It” by the Walter Family, an instrumental recorded when the musicians weren’t aware that the mic was turned on. It has the loose feel of a rehearsal, which in fact it was. The band members chime in on an array of instruments, beginning with Draper Walter’s lone fiddle, then his wife on piano, then a guitar, a banjo, a washboard, and finally a jug—like a family jam session moving through the house and picking up players along the way, from the parlor to the kitchen to the porch. Recorded in 1933 at the height of the Depression, there is only one known copy (it’s available on the new Kentucky Mountain Music box set on Yazoo).

What destroyed this Golden Age, according to King, were advances in the music industry made after World War II, in particular the advent of amplified instruments and the A&R men who marketed music. In a purer time, King says, “you only had your voice and your instrument to produce the dynamics. That changed in the late ’40s and early ’50s with amplification. They had all these studio gadgets they pulled out, and it diminished the artistry. There’s a good analogy my dad always told me. Back in the ’20s and ’30s, they couldn’t afford a nice Martin guitar or a good Gibson mandolin; they were playing Sears & Roebucks and Stellas—Patton played on a fucking Stella and he could take that instrument and pull out more notes and rhythms than a person nowadays with the most expensive guitar could ever dream of.”

This standard, of course, means that few artists make the cut. Hank Williams? A singer from Alabama sabotaged by Nashville studios; even Jimmie Rodgers, the father of country music, had only three songs that aren’t too uptown for King’s tastes. Today’s so-called alt-country rebels are delusional poseurs beneath his contempt. “The alternative country scene is a twenty-five-year-old hippie girl backed by a lap steel,” he says. “There’s nothing going on. It’s urban people who sing about drinking and adultery and horseshit like that. It’s second- or third-generation swill. Somebody was playing me an alternative country band and this woman singer was really trying to put on this affected, twangy accent and it was just miserable—it made me just want to scream and tear my head off.” The only contemporary music King can stomach—besides traditional bluegrass—are stubborn iconoclasts like Sonic Youth and Cypress Hill and Tom Waits.

“Did you hear that Tom Waits said the Charley Patton set was his favorite album of all time?” says King. “He said he couldn’t keep a copy because he kept giving it to his friends.”

Driving in King’s pick-up truck, out hunting for old records, we pass a ramshackle spread where a neighbor has set up a makeshift flea market on a knoll near his driveway. A tent keeps the wares dry, but it doesn’t block the cold. The neighbor is a chronic scavenger, retrieving furniture and knickknacks that people take to the dump, then selling the stuff back to other neighbors and anyone else who happens to drive by. “He has a chair we threw out,” says King. “I’ve bought records from him. Some Bill Monroe on Columbia.”

King spends a lot of time trolling yard sales and junk shops. He posts fliers around the area (PRIVATE COLLECTOR WILL PAY CASH FOR OLD “VICTROLA” RECORDS) to flush out 78s from the surrounding countryside. Not far away, over the state line in West Virginia, King has come across some of his greatest finds in a remote county he won’t reveal. That state, he says, is still the best region to find 78s in private homes because of so many self-sufficient farmers who had money for Victrola records at the time. But even here in Nelson County, just a few miles southwest of Charlottesville, the rolling hills are planted with large Victorian farmhouses, the ones that often hold untold riches of hillbilly records. For the old folks who hesitate to sell, because they actually still use their Victrolas, King brings along a box of junkers, which he offers as replacements for a record he’s after.

Outside Lovingston, the county seat, near an abandoned train depot, we pull up to an antiques store King wants to check out. It’s not much more than a wooden shack, with dusty windows full of junk. Today it’s closed, but for King such disappointments are commonplace.

He mentions a mother and daughter his wife Charmagne recently told him about. The mother’s in her nineties. The rumor is that they’ve got 78s. They both live just down the road. But the weather makes for bad business. “It’s persistence,” King says, “and knowing when’s the right time to put the hammer down, because so many people jump the gun. For instance, I might bug those old ladies to ask them about records in the middle of winter, and they’re going to look at me like I’m a knife-wielding lunatic. But if I wait until the spring when the birds begin to sing and the ground is dry and it’s warm, and if I go over there and say, ‘I’m wondering if you had any old Victrola records?’ They might sell ’em to me. It’s knowing when to do things.”

Winter holds him back for now. When the weather breaks, he’ll pay the ladies a visit.